Installation

The extraction tool needs to be built from source. This is because the harness definitions depend on

the circuits crate in midnight-zk.

Once inside of the directory where the source is located you can build and run the tool.

First, verify that the version of midnight-circuits that the tool is linked against

is the version you are interesting in extracting from.

Check that the dependency is pointing to the right repository and the right revision.

Also make sure that it has the extraction feature enabled. Without this feature the

circuits do not include the necessary integrations.

For example:

$ cargo info midnight-circuits

midnight-circuits

version: 5.0.1 (from https://github.com/Veridise/midnight-zk#0d63a4d4)

license: unknown

rust-version: unknown

features:

+default = []

bench-internal = [midnight-proofs/bench-internal]

extraction = [extractor-support, testing, midnight-proofs/extraction, picus/extractor-derive]

extractor-support = [dep:extractor-support]

heap_profiling = []

serde = [dep:serde]

serde_derive = [dep:serde_derive]

serde_json = [dep:serde_json]

testing = [num-bigint/rand]

truncated-challenges = [midnight-proofs/truncated-challenges]

Once everything looks good you can build the tool as usual with cargo build --release.

Extraction

Once the tool is build you can use the midnight-extractor CLI to extract the circuits.

Quickstart

To extract all the circuits you can use the extract-all.sh script located in the scripts directory.

The Picus representation of the extracted circuits can be found in the picus_files directory.

By default this tool does not extract the LLZK versions.

CLI usage

The midnight-extractor CLI builds a list of extractable circuits at runtime then extracts them to the desired format.

The CLI has a series of flags and arguments that allows controlling the selection of circuits to extract. The CLI also has

flags for controlling the output produced by the tool.

Use the --help flag to see the full list of options.

Circuit selection

Each circuit has 4 properties that are used for filtering and selection; instruction, chip, type, and name.

The instruction groups together circuits that are related and in general corresponds to an instruction-like trait

(i.e. arithmetic corresponds to ArithInstructions or ecc to EccInstructions). The instructions are selected as

positional arguments. Adding instructions to the CLI invocation creates a set of selected instructions. If no

instructions are passed to the CLI then all instructions are considered.

Possible instruction values: arithmetic, assertion, assignment, automaton, base64, base64-var, biguint, binary, bitwise, canonicity, committed-instance, comparison, control-flow, conversion, core-decomposition, decomposition, division, ecc, equality, field, foreign-ecc, hash, hash-to-curve, map, map-to-curve, parser, pow2-range, public-input, range-check, sha256, sponge, stdlib, unsafe-conversion, varhash, vector, zero.

The chip declares what concrete implementation of the instruction is used by the circuit. Different chips

implement the same instruction traits and this parameter allows configuring what chip is going to be targeted.

To select a chip use the --chip <name> flag. This will make the tool filter out any circuit that is not implemented

by the chip. If the flag is not passed then the tool will consider all chips.

Possible chip values: native, native-gadget, field, poseidon, pow2-range, p2r-decomposition, sha256, ecc, foreign-ecc-native, foreign-ecc-field, vector, biguint, stdlib, automaton, base64, hash-to-curve, map, parser, varlen-poseidon, varlen-sha256.

The type declares what high-level type the circuit is using and can be selected with the --type <name> flag.

Similarly to --chip, not passing this flag makes the tool consider all types. The circuits distinguish by type

because some circuits implement the same instructions for multiple. For example, the native chip implements

the equality instructions for the native and bit types.

Possible type values: native, bit, field, byte, biguint, scalar, point.

The name describes the functionality the circuit is trying to represent. In general corresponds to methods in

one of the instruction-like traits. Some methods have a variable number of arguments. In cases like that

then multiple circuits may be created with different combinations of arguments and the name will contain information

about the combination (i.e. the circuits hash/hash_1/sha256/byte and hash/hash_10/sha256/byte operate on 1 and 10

input values respectively).

You can filter by name with both a whitelist and a blacklist. If the whitelist is passed,

any circuit outside of the list is discarded. And, if the blacklist is passed, then any circuit inside it is discarded.

If the whitelist or the blacklist are not set then they have no effect and all circuit names will be included in the

extraction. Both lists can be configured as a comma separated list passed as arguments to the --method-whitelist and

--method-blacklist flags.

You can combine these flags in any way you want. You can also pass the --list flag to the tool makes it print the

selected circuits instead of extracting them. This is useful for debugging a circuit selection that is not producing the

desired results.

Constants

Some harnesses require a list of literal values that will be used as compile-time constants representing

off-circuit values in the harness’ input. To pass constants use either --constants or --constants-file.

The former expects a comma separated list of literal values. All types expect their decimal representation with the

exception of bit with expectes either true or false. The latter expects a path to a file containing lines

of comma separated values. These values have the same requirements as the --constants flag.

If a harness requires more constants than supplied extraction will fail.

Output directory structure

The output directory can be selected with the -o flag and if the flag is omitted picus_files is used as a default.

The tool writes into this directory one Picus file per extracted harness. These files are organized hierarchically

by instruction, name, chip, and type. For example the harnesses for equality in the native chip will produce

the following structure.

└── picus_files

└── equality

├── is_equal_to

│ └── native

│ ├── bit

│ │ └── output.picus

│ └── native

│ └── output.picus

└── is_equal_to_fixed

└── native

├── bit

│ └── output.picus

└── native

└── output.picus

AuditHub

AuditHub is a Veridise service where users can run verification tools such as Picus. Is accesible via both its web interface and CLI. In this document we will explain how to prepare a project for AuditHub, how to configure the CLI, and how to use it for interacting with AuditHub.

AuditHub CLI

The CLI is a Python 3 program that can be installed with pip (pip install audithub-client).

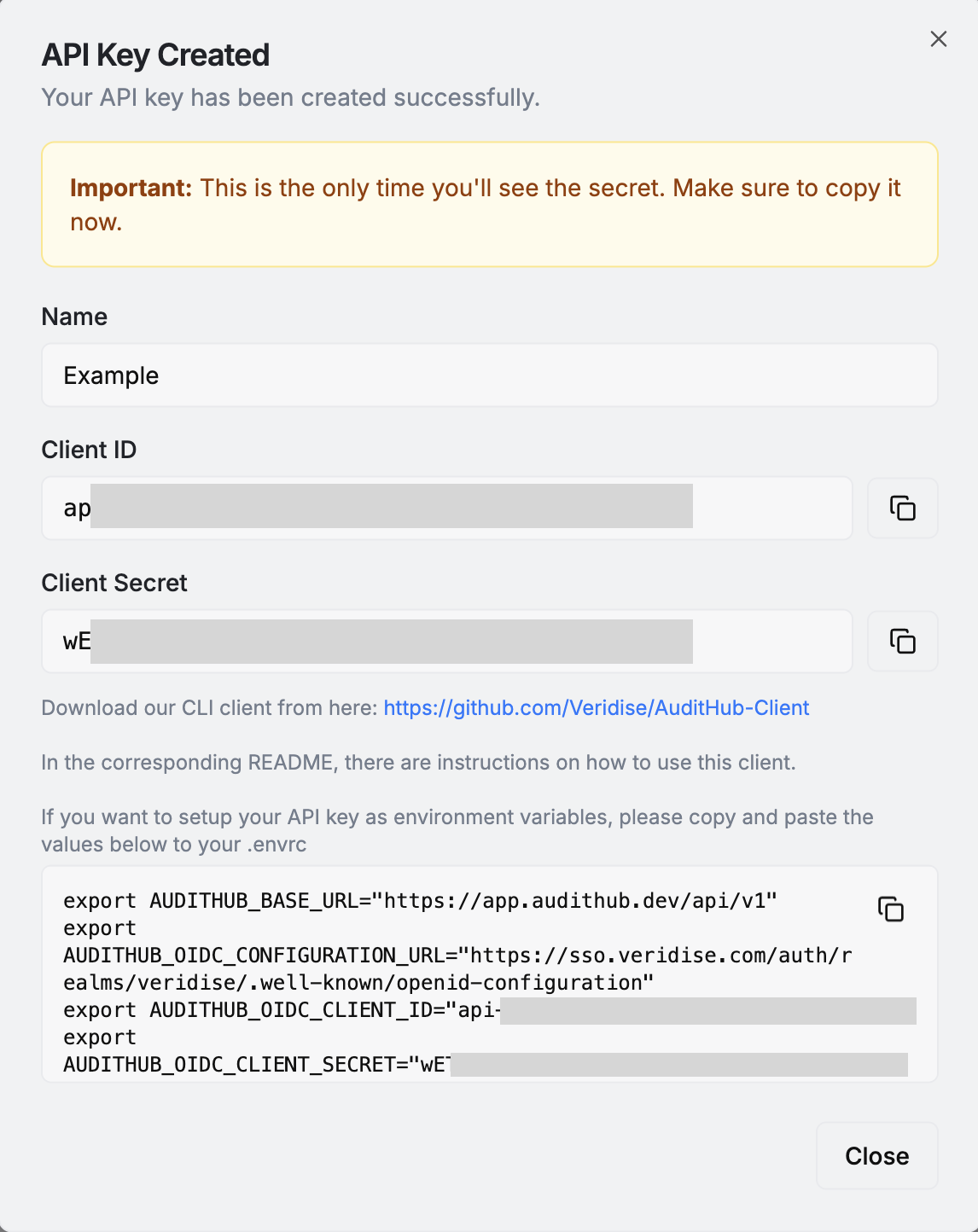

The CLI needs to be configured before using it. For that go to Account Settings / API Keys in AuditHub’s UI. Store the given client id and client secret somewhere secure depending on the intended usage of the keys.

For using the keys locally it could be a .envrc file

managed by direnv. For using them in CI that could be Github Secrets accesible

by Github Actions.

Once the keys are ready check the CLI’s documentation on how to configure you system such that the CLI can use them to connect to AuditHub.

You can confirm that the CLI is working correctly by running the following

$ ah get-my-profile

{"id": "...", "name": "<Your name>", "email": "<Your email>", "rights": [...], ...}

Creating a new project

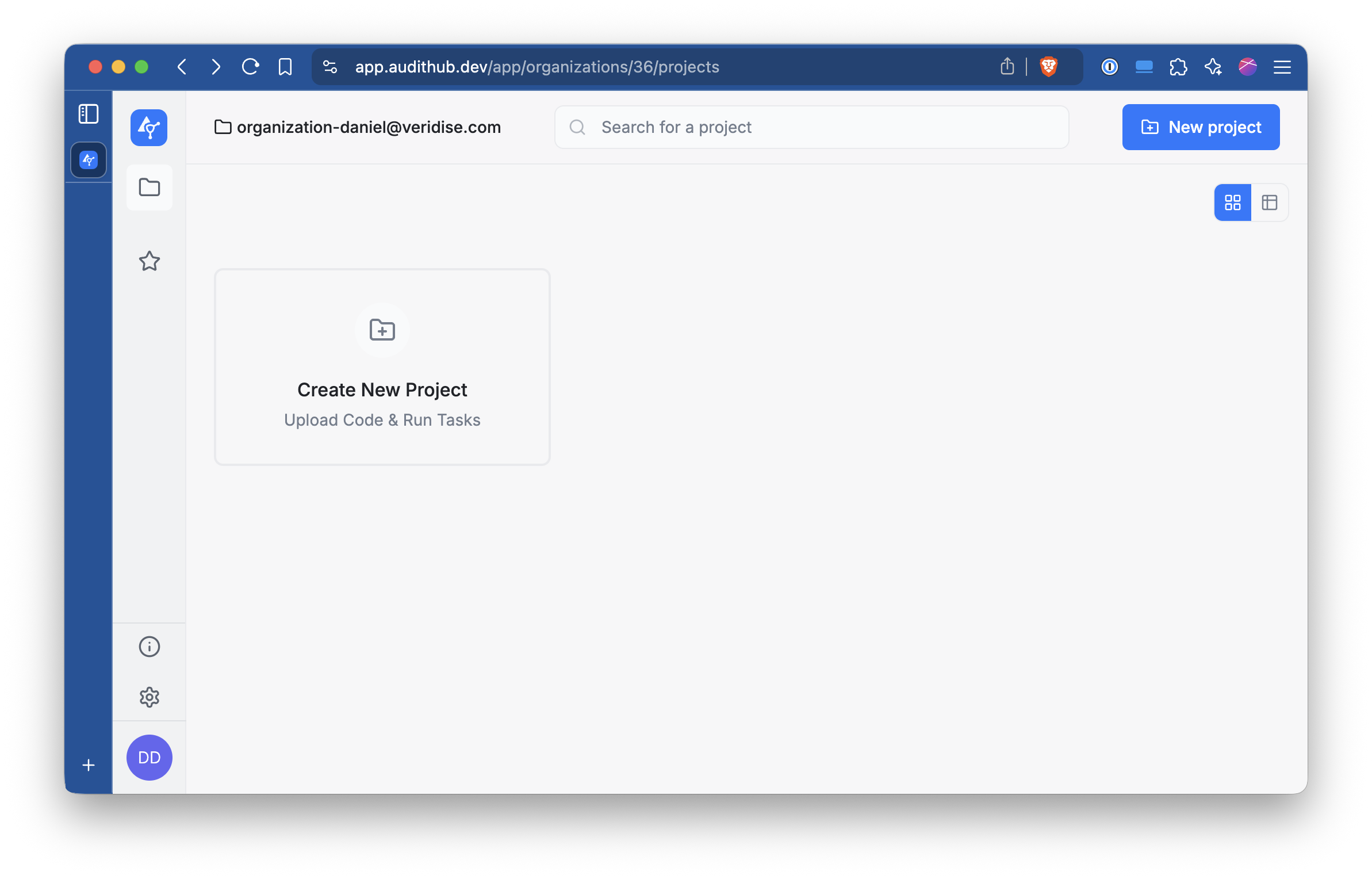

Before being able to upload new versions to AuditHub and launch jobs from the CLI it is necessary to create a project from the UI.

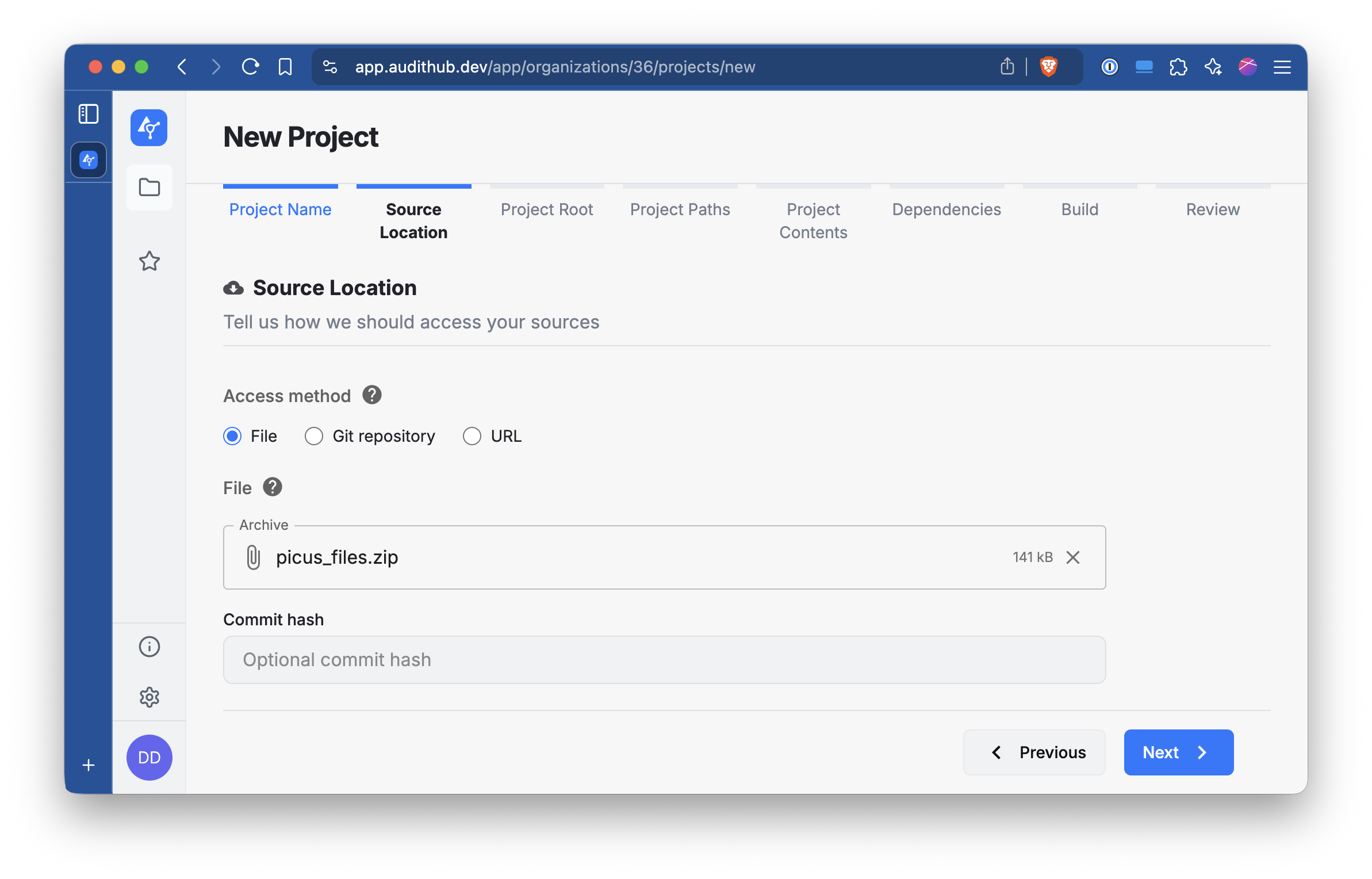

For the first version of the project generate at least some Picus files with midnight-extractor and pack them into a ZIP file.

# For example, generate some Picus files for the equality instructions

cargo run --release -- --chip native --type native equality

zip -r picus_files.zip picus_files

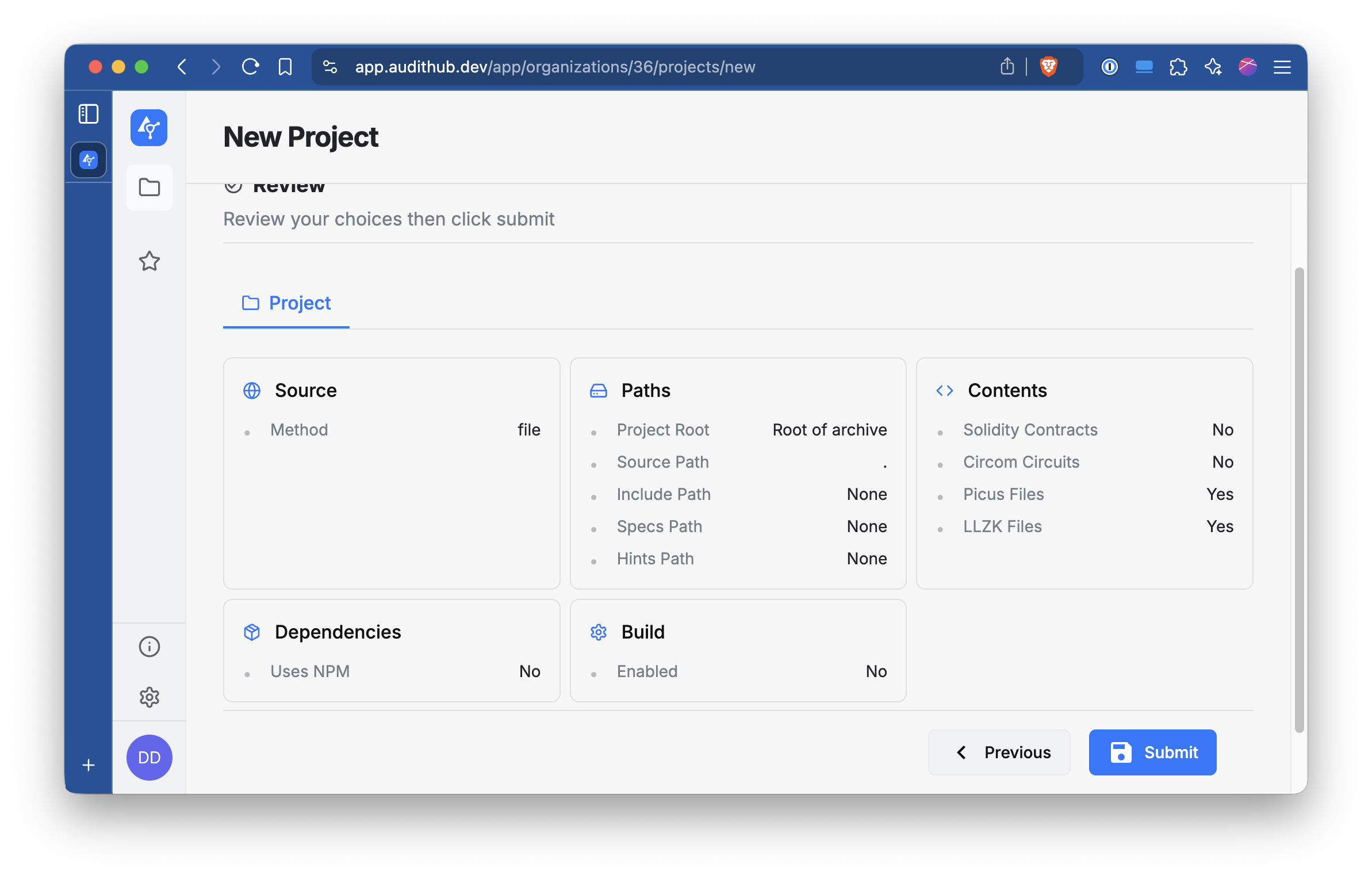

Then go to AuditHub’s UI and into the organization where you want to create the project and click in Create New Project

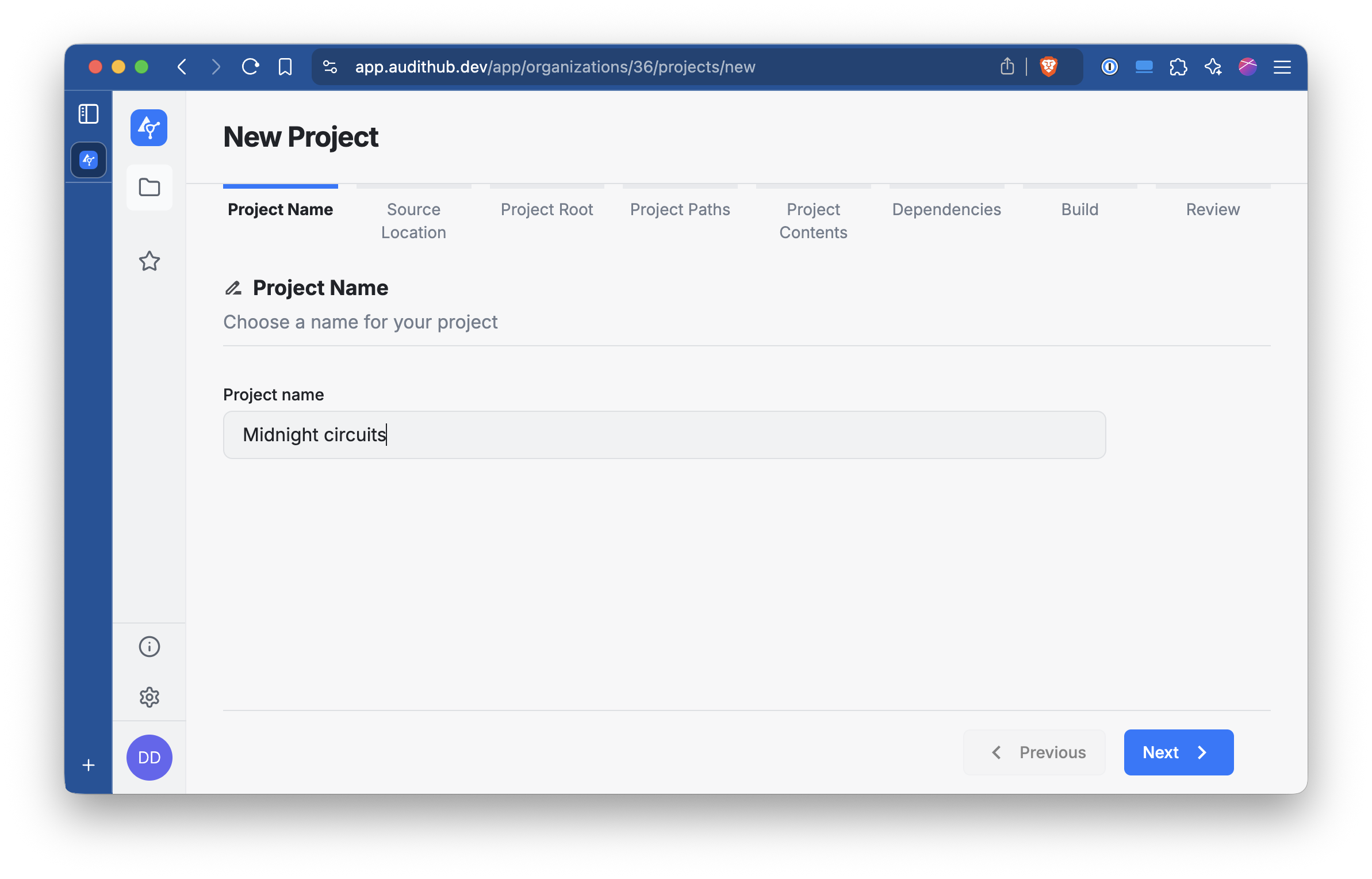

Given a name to the project and click Next.

Select the File option and locate the ZIP file prepared earlier. Once you have it click Next.

Select Archive root and click Next.

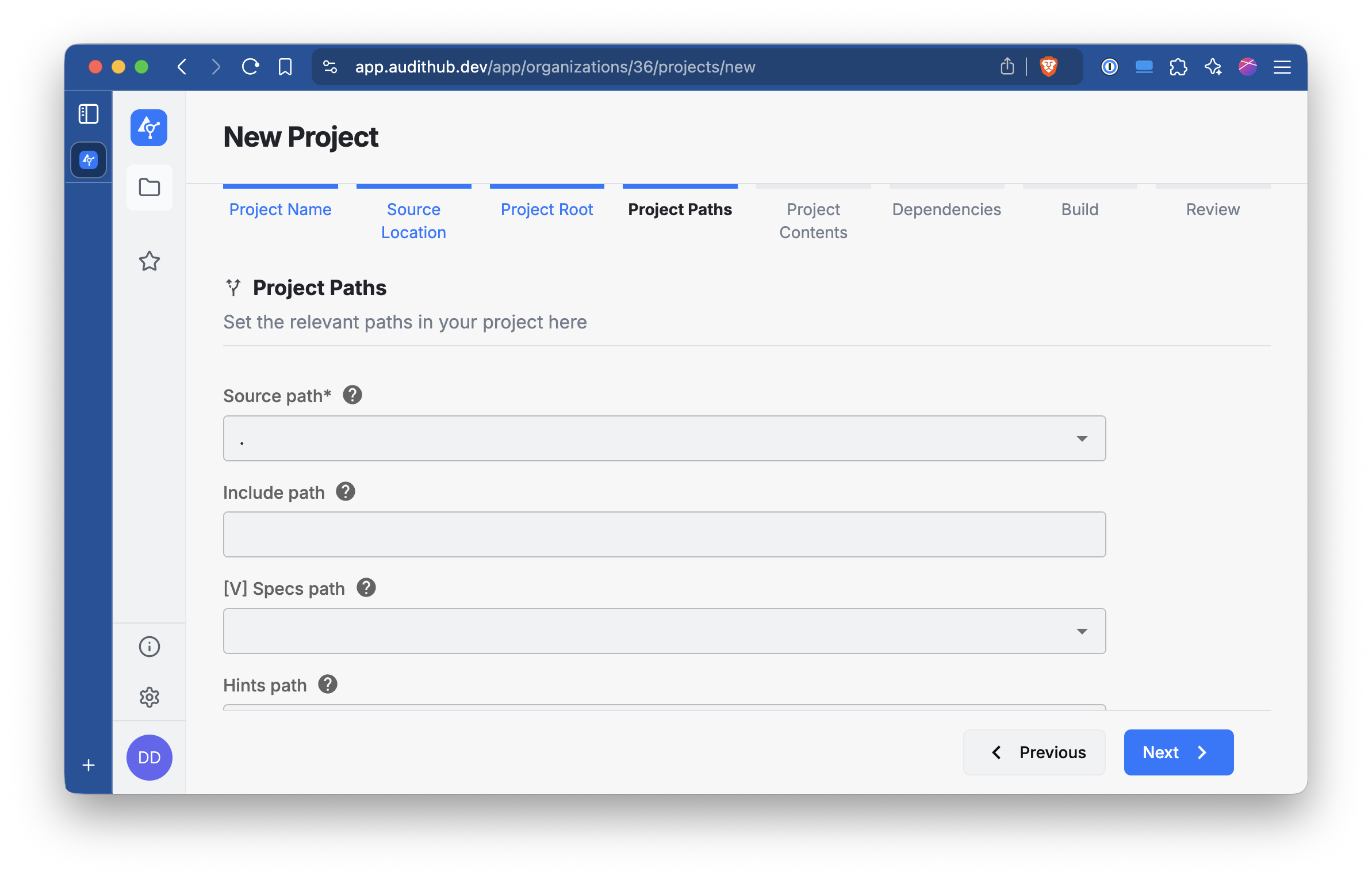

In this section, leave this options as they are and click Next.

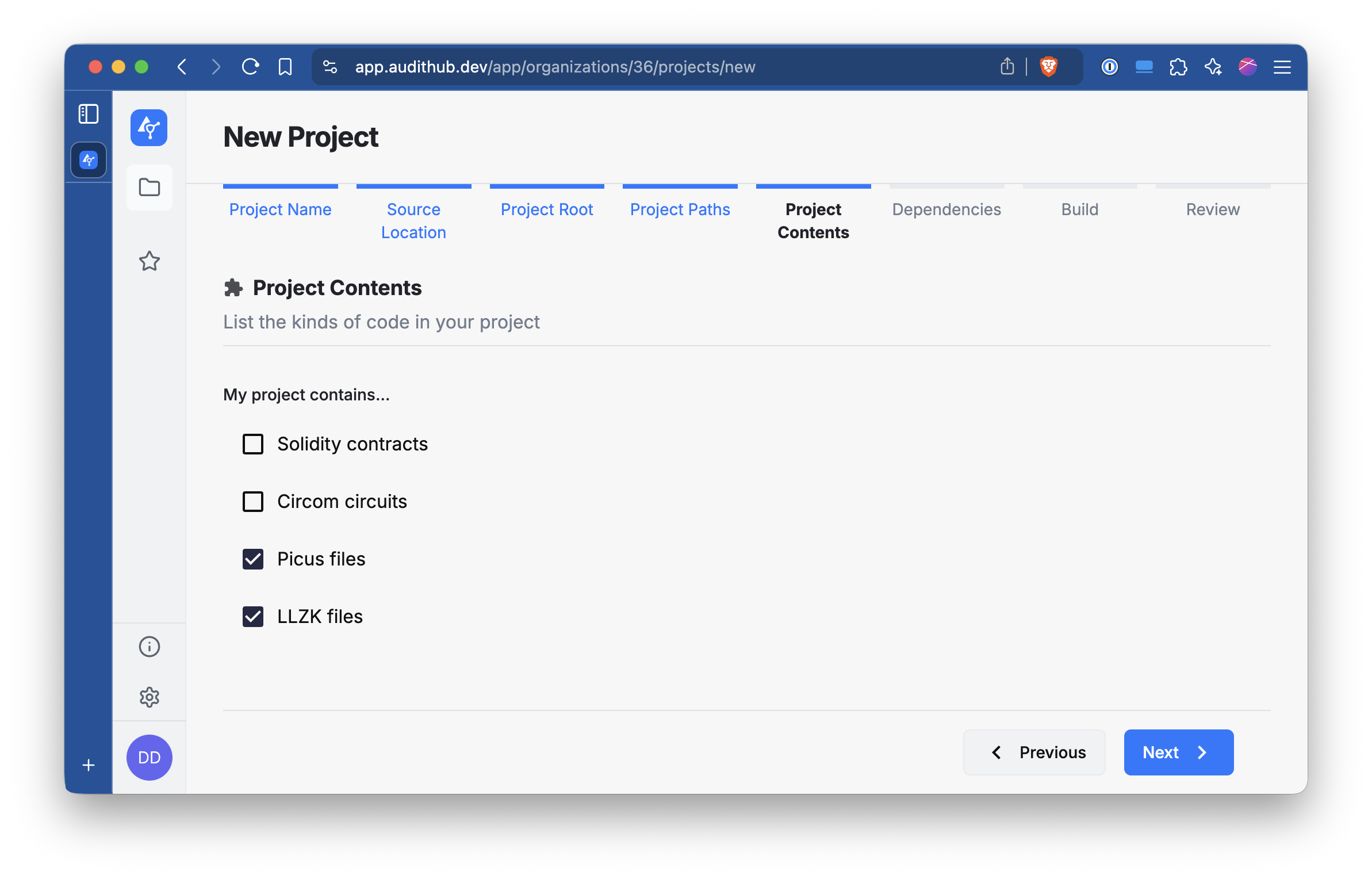

Select Picus files (and optionally LLZK files) and click Next.

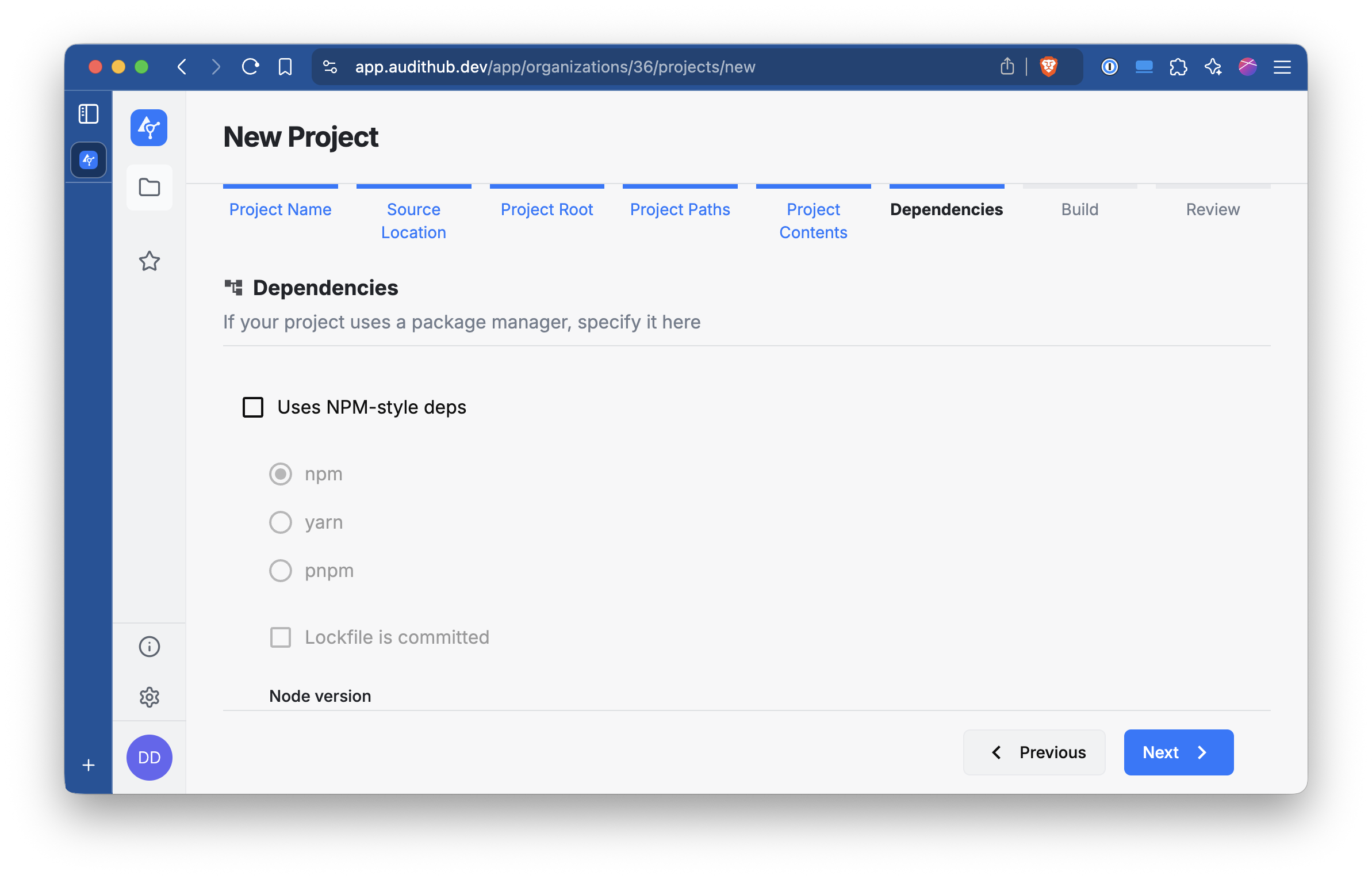

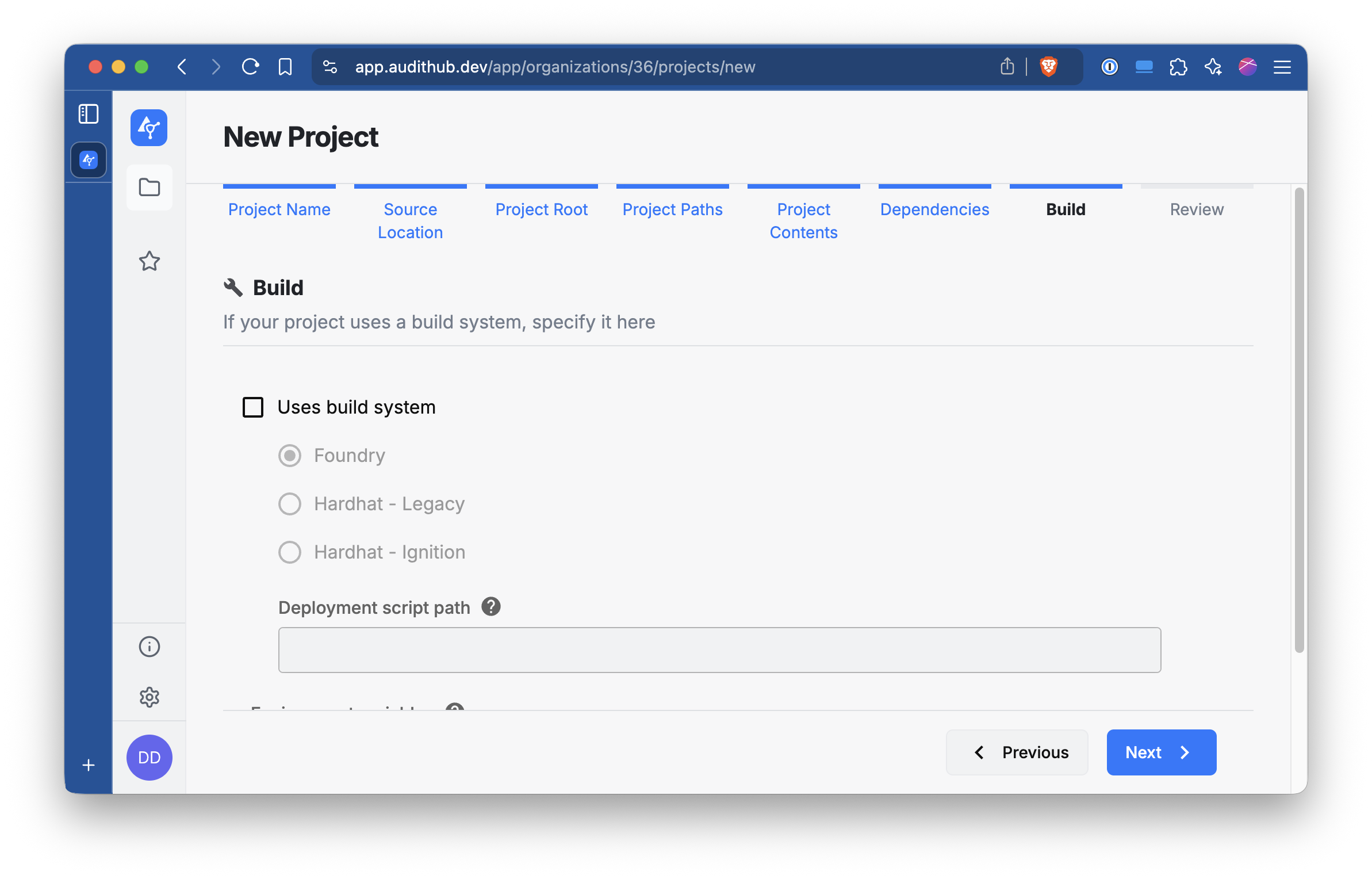

Leave the next two sections untouched and just click Next.

Check that everything looks right and click Submit.

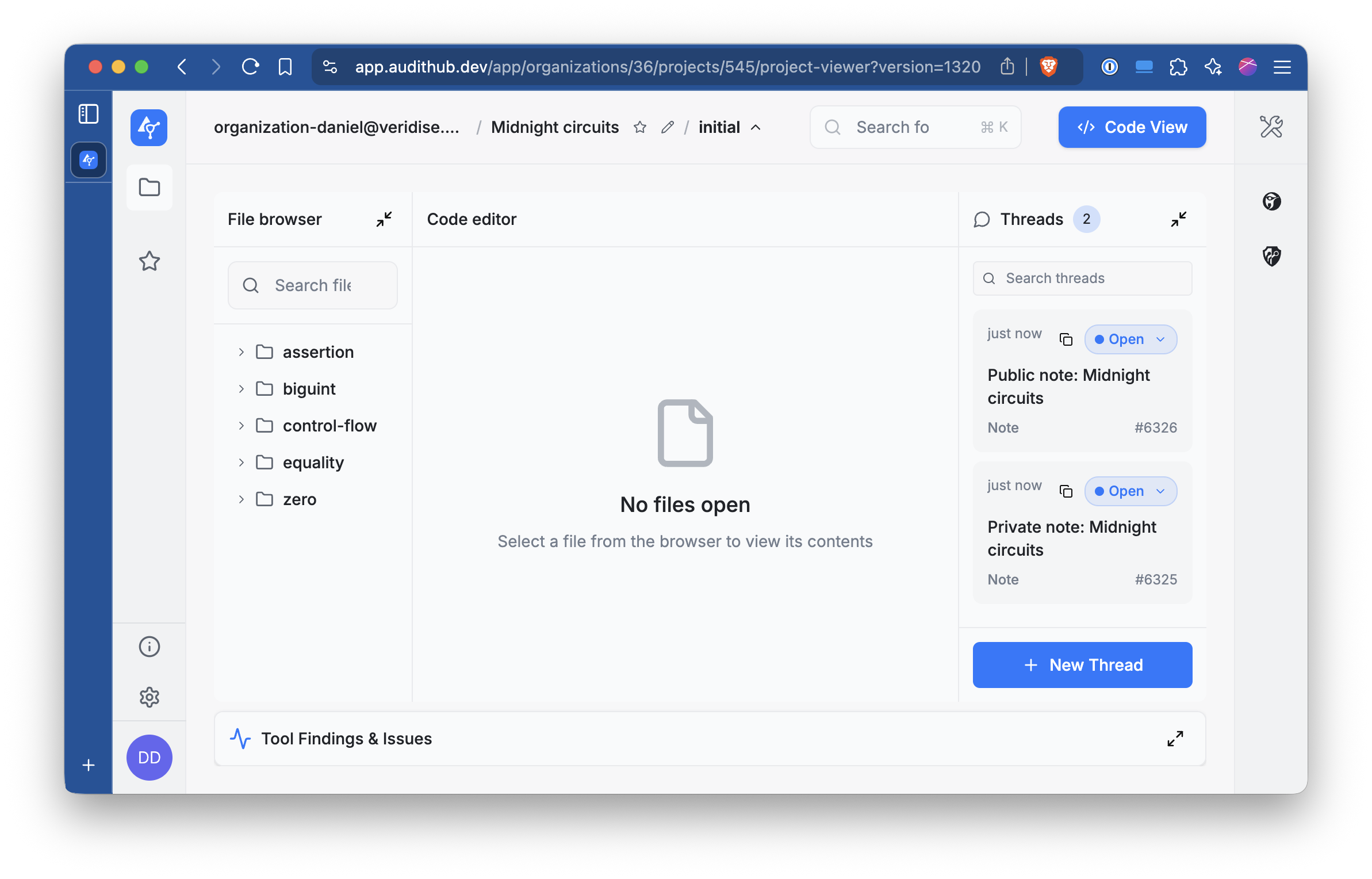

Once the project has been created you will be able to access its main view. For interacting with this

project from the CLI you need to pass the organization and project IDs. Note in the part of the URL

organizations/<number>/projects/<number>. The first is the organization ID and the second the project ID.

These IDs can be configured as environment variables and the CLI will use them while executing.

export AUDITHUB_ORGANIZATION_ID=<organization id>

export AUDITHUB_PROJECT_ID=<project id>

Uploading new versions

Make sure you went through the steps in Creating a new project before continuing.

After extracting a new version of the circuits but before running Picus with them, they need to be uploaded to AuditHub. This can be accomplised with either the UI or with the CLI. In this document we are going to see how to do it with the CLI, what you should have previously configured.

Each version needs to have a name. As an example we are going to use the date of submission and the

sha256 of the generated picus files.

From the shell run the following, assuming the picus files are in the default output folder (picus_files).

date=$(date "+%Y-%m-%d-%H-%M")

sum=$(find picus_files -type f | sort | xargs cat | sha256sum | head -c 8)

version_id=$(ah create-version-via-local-archive \

--name "Picus-files-$date-$sum" \

--source-folder picus_files \

--project-id $PROJECT_ID \

--organization-id $ORGANIZATION_ID)

If you configured the AUDITHUB_PROJECT_ID and AUDITHUB_ORGANIZATION_ID environment variables

you can drop the --project-id and --organization-id flags since the CLI can read them from the environment.

Note that we stored the output of the CLI in a variable named $version_id. We need this for identifying the

version when launching jobs.

Launching jobs

Once you have uploaded a version of the extracted circuit to AuditHub you can start running tools with them.

We are going to see how to launch a Picus job from the CLI. Each individual Picus file needs to be run as a separate task. Pick one of the Picus files in the version you last uploaded and note its path relative to the directory you uploaded it from. For example, to run a job for up to one hour run the following in the shell.

# Example path that could be extracted

PICUS_FILE=arithmetic/add/native/native/output.picus

ah start-picus-v2-task \

--source $PICUS_FILE \

--version-id $version_id \

--project-id $PROJECT_ID \

--organization-id $ORGANIZATION_ID \

--time-limit 3600000 \

--empty-assume-deterministic \

--wait

This will wait until the job has completed in AuditHub. If the --wait flag is dropped the CLI returns immediately,

responding with the task ID. This ID can be passed to ah monitor-task -t $task_id for checking the status of the task.

You can run

ah start-picus-v2-task --helpto get more details about the possible flags and arguments.

Similarly to the upload, if you configured the AUDITHUB_PROJECT_ID and AUDITHUB_ORGANIZATION_ID environment variables

you can drop the --project-id and --organization-id flags since the CLI can read them from the environment.

Picus requires a bit of configuration

in some cases; if you passed the --prelude flag while extracting circuits with either spread

or automaton then you need to pass additional flags.

| Prelude | Additonal Picus flags |

|---|---|

spread | --assume-deterministic Spread,Unspread |

automaton | --assume-deterministic Automaton |

| None | --empty-assume-deterministic |

Writing new harnesses

Adding more harnesses is done in the crates/harnesses crate. The crate is organized by instructions and,

in some cases, by chips or gadgets that implement the instructions.

Conceptually, a harness is a function that receives a chip, a layouter, some inputs and returns a Result.

In reallity a harness is a function with a more abstract signature but that complexity is usually managed by a macro

that allows for a more declarative approach. However, if the macro is not an option see the section below

on how to write harnesses from scratch.

Writing declarative harnesses

A harnesses written declaratively has the following structure.

#![allow(unused)]

fn main() {

// The harnesses are NOT parametrized by a field.

use mdnt_extractor_core::fields::Blstrs as F;

// Sets the harness name of the function below.

#[entry("control-flow/select/native/native")]

// Marks the function as a harness

#[harness]

pub fn select_native(

// The first argument is the chip. The only requirement is that the type is a &-reference.

chip: &NativeChip<F>,

// The second argument is the layouter. The actual layouter variable is not a

// `impl Layouter<F>`. This is syntactic sugar for a namesake variable that

// implements `midnight_proofs::circuit::Layouter`. So the result is the same.

layouter: &mut impl Layouter<F>,

// The third argument are the inputs. The type of the input must implement `LoadFromCells`.

(cond, a, b): (AssignedBit<F>, AssignedNative<F>, AssignedNative<F>),

// Optional fourth argument that allows injecting additional IR for aiding verification.

injected_ir: &mut InjectedIR<RegionIndex, Expression<F>>

// The output must be a Result<T, E> where T is a type that implements `StoreIntoCells` and

// E is `midnight_proofs::plonk::Error`.

) -> Result<AssignedNative<F>, Error> {

// Runs the target method.

chip.select(layouter, &cond, &a, &b)

}

}And that’s it. The list of harnesses is defined automatically at compile time and

can be obtained by calling the mdnt_harnesses::harnesses function.

The extractor uses that function for selecting what harnesses need to be extracted.

The macros do a lot of heavy lifting in converting this form to how the harnesses look internally.

The #[entry("...")] macro registers the function in the list of harnesses. This registration is accomplised

with mdnt_extractor_core::entry! and in some cases is actually better to use this macro instead of #[entry].

For example, a harness that is parametrized by a constant parameter for selecting the size of some arrays.

#![allow(unused)]

fn main() {

entry!("bar/example_10/foo/native", example::<10>);

entry!("bar/example_20/foo/native", example::<20>);

#[harness]

pub fn example<const N: usize>(

chip: &FooChip<F>,

layouter: &mut impl Layouter<F>,

arr: [AssignedNative<F>; N]

) -> Result<AssignedNative<F>, Error> {

chip.foo(layouter, &arr)

}

}The harness macro family has 6 macros that can be used for declaring harnesses and offer some flexibility for covering most cases.

For most chips (the ones where ChipArgs::Args == ()) use the macros harness, harness_mut, and unit_harness. The

first macro is the one we saw above already. harness_mut is similar to harness but the first argument (the chip argument)

must be a &mut-reference instead. unit_harness is for methods that do have a return value (Result<(),Error>). For this

macro split the inputs of the function into two sets and pass them as the 3rd and 4th argument. The 4th argument can be

considered the output and additional constraints can be injected for aiding Picus with verification. That argument, however,

is not encoded as a Picus output. Is just a separation for readability. In these cases a vacuous output is generated

that is constrained to be equal to 0.

If for the target chip ChipArgs::Args != () then you need to use harness_with_args, harness_with_args_mut, and

unit_harness_with_args. These macros work identically to their counterparts but require declaring the type of

ChipArgs::Args (i.e. #[harness_with_args(usize)]). For providing the argument you need to define a function that has

the same name as the harness function followed by _args (i.e. foo would be foo_args). That function cannot take any

arguments and return a value of the declared type.

Since the most common argument type is usize we include a convenience macro #[usize_args(<usize>)] that automatically creates

the function with the correct name and returns the value passed as argument to the macro.

All the macros accept an optional argument with an expression containing LookupCallbacks. For example, for extracting a

harness like the first one but for NativeGadget instead we need to handle the range lookup that gadget uses. For that we can

do as follows:

#![allow(unused)]

fn main() {

#[entry("control-flow/select/native-gadget/native")]

// The range_lookup function creates the appropiate handler for the lookup.

#[harness(range_lookup(8))]

pub fn select_native(

chip: &NG<F>,

layouter: &mut impl Layouter<F>,

(cond, a, b): (AssignedBit<F>, AssignedNative<F>, AssignedNative<F>),

) -> Result<AssignedNative<F>, Error> {

chip.select(layouter, &cond, &a, &b)

}

}Writing harnesses from scratch (WIP)

If the macros shown above don’t fit the needs of this new harness they can still be defined by hand. Below is an annotated version of the kind of code the macros generate that can serve as a starting point for creating a harness from scratch.

#![allow(unused)]

fn main() {

entry!("control-flow/select/native-gadget/native", select_native);

fn select_native(ctx: &Ctx) -> anyhow::Result<Output> {

// The actual logic of the harness needs to be wrapped into a trait.

// So we need to create a type for that.

struct Circuit<'s, 'c>(PhantomData<(&'s (), &'c ())>);

// This trait defines the types that the harness uses.

// The extractor will rely on this trait for finding the right types for

// creating the right final circuit.

impl<'s, 'c> AbstractCircuitIO for Circuit<'s, 'c> {

// The chip type. It must implement CircuitInitialization but is not enforced.

type Chip = NativeChip<F>;

// The type of the inputs. Must implement `LoadFromCells` and if the method takes several

// they can be grouped in tuples up to 12 elements.

type Input = (AssignedBit<F>, AssignedNative<F>, AssignedNative<F>);

// The type of the outputs. Same as the inputs but must implement the

// `StoreIntoCells` trait instead.

type Output = AssignedNative<F>;

// These two types need to be the same as their namesakes in CircuitInitialization.

type Config = <NativeChip<F> as CircuitInitialization<ExtractionLayouter<'s, 'c, F>>>::Config;

type ConfigCols =

<NativeChip<F> as CircuitInitialization<ExtractionLayouter<'s, 'c, F>>>::ConfigCols;

}

// The actual logic is defined with this trait.

// `harness_mut` will use `AbstractCircuitMut`

impl AbstractCircuit<F> for Circuit<'_, '_> {

fn synthesize<L>(

&self,

chip: &Self::Chip,

layouter: &mut L,

(cond, a, b): Self::Input,

_: &mut InjectedIR<

RegionIndex,

Expression<F>,

>,

) -> anyhow::Result<Self::Output, Error>

where

L: Layouter<F>,

{

chip.select(layouter, &cond, &a, &b)

}

}

// If the chip arguments is () then this trait can be used.

impl NoChipArgs for Circuit<'_, '_> {}

// The type we created and implemented the types for can be passed to this

// type. This type handles the linking between the inputs, outputs, and the harness logic.

let ci: CircuitImpl<'_, F, Circuit, Function> =

CircuitImpl::new(ctx, Circuit(Default::default()));

// The first argument of this method is a type that implements the

// CircuitSynthesis trait, which is Haloumi's counterpart to the Circuit trait in Halo2.

// As long as the value passed there meets the interface all the stuff above this line is not

// mandatory.

// The second argument is an optional dyn reference to a LookupCallbacks implementation.

// These callbacks are invoked when the circuit has lookups for getting the IR that needs to be

// generated for handling the lookup.

ctx.lower_circuit(ci, None)

}

}Supporting new chips

In order to use user defined chips or gadgets in a harness it is necessary to implement a trait. This trait makes the chip or gadget compatible with the extraction system.

Let’s do a small refresher on why this is necessary. A harness can be defined as follows.

#![allow(unused)]

fn main() {

#[entry("control-flow/select/native/native")]

#[harness]

pub fn select_native(

chip: &NativeChip<F>,

layouter: &mut impl Layouter<F>,

(cond, a, b): (AssignedBit<F>, AssignedNative<F>, AssignedNative<F>),

) -> Result<AssignedNative<F>, Error> {

chip.select(layouter, &cond, &a, &b)

}

}This harness targets the NativeChip. When the extractor attempts to extract the harness it needs to know

some things about this chip, but it doesn’t know what the NativeChip is. This information is obtained via the

CircuitInitialization trait.

This trait, similar in nature to Halo2’s Circuit trait, enables the extractor to configure and create chips that implement it.

Let’s consider the following chip as an example.

#![allow(unused)]

fn main() {

struct FooConfig {

advice: [Column<Advice>; ADVICE_WIDTH],

fixed: [Column<Fixed>; FIXED_WIDTH],

table: [TableColumn; TABLE_WIDTH]

}

struct FooChip<F> {

config: FooConfig,

native: NativeChip<F>

}

impl<F: PrimeField> FooChip<F> {

fn configure(meta: &mut ConstraintSystem<F>) -> FooConfig {

// Create an instance of the config...

}

fn new(config: FooConfig, native: NativeChip<F>) -> Self {

Self { config, native }

}

fn load_table(&self, layouter: impl Layouter<F>) -> Result<(), Error> {

// Loads the lookup table...

}

}

}Our example chip has a lookup table and depends on NativeChip, which already implements the trait we are going to implement.

The trait is parametrized in L, that we can use as an implementation of a Layouter.

#![allow(unused)]

fn main() {

impl<F, L> CircuitInitialization<L> for FooChip<F>

where

F: PrimeField,

L: Layouter<F>,

{

// Type that is generated from the ConstraintSystem, usually the Chip's config.

type Config = (FooConfig, <NativeChip<F> as CircuitInitialization<F>>::Config);

// Any external arguments the chip may need. If the chip does not have any then

// a 0-tuple is sufficient.

type Args = ();

// Any type that is part of the configuration that could be potentially shared with other chips.

// This should have any type, potentially created by the ConstraintSystem, but that is not created by the chip itself.

// FooChip does not have any of that in this case so we just put NativeChip's.

type ConfigCols = <NativeChip<F> as CircuitInitialization<F>>::ConfigCols;

// These two types are required because mdnt-support does not have a dependency on any

// halo2 library. We need to declare what types are used as ConstraintSystem and as Error.

// Usually these will be the types `<halo2-crate>::plonk::{ConstraintSystem, Error}`.

type CS = ConstraintSystem<F>;

type Error = Error;

/// Initializes a new chip with the given config and arguments, if any.

fn new_chip((config, native_config): &Self::Config, _: Self::Args) -> Self {

Self::new(config, NativeChip::new_chip(native_config, ()))

}

/// Creates a new configuration.

fn configure_circuit(

meta: &mut Self::CS,

config_cols: &Self::ConfigCols,

) -> Self::Config {

(Self::configure(meta), NativeChip::configure_circuit(meta, config_cols))

}

/// Performs any required loading, such as lookup tables.

/// This method is called by the extractor after the harness' method has been executed.

fn load_chip(&self, layouter: &mut L, (_, native_config): &Self::Config) -> Result<(), Self::Error> {

self.load_table(layouter)?;

self.native.load_chip(layouter, native_config)

}

}

}With this trait implemented the type can now be used as the chip argument in any harness.

Supporting new assigned types

In order to use user defined types as inputs or outputs in a harness it is necessary to implement some traits. These traits make the type compatible with the extraction system.

Let’s do a small refresher on why this is necessary. A harness can be defined as follows.

#![allow(unused)]

fn main() {

#[entry("control-flow/select/native/native")]

#[harness]

pub fn select_native(

chip: &NativeChip<F>,

layouter: &mut impl Layouter<F>,

(cond, a, b): (AssignedBit<F>, AssignedNative<F>, AssignedNative<F>),

) -> Result<AssignedNative<F>, Error> {

chip.select(layouter, &cond, &a, &b)

}

}In this example the type (AssignedBit<F>, AssignedNative<F>, AssignedNative<F>) is the type

of the input and AssignedNative<F> is the type of the output. When lowering to Picus we cannot use

this types directly because PCL does not support user defined types and everything is a felt. The extractor

works around this issue by creating two auxiliary tables (one for inputs and another for outputs) that represent

the inputs and outputs of the circuit as individual cells. In the example above we need 3 cells in the input auxiliary

table and 1 cells in the output auxiliary table. We know this because AssignedNative<F> is an alias over Halo2’s

AssignedCell<F,F> and AssignedBit<F> wraps an AssignedNative<F>.

As a running example, we are going to add support to the following type as we explain the concepts.

#![allow(unused)]

fn main() {

struct AssignedFoo<F> {

foo: [AssignedNative<F>; 10],

bar: AssignedBit<F>

}

}In order for the extractor to know how many cells a type occupies we have the CellReprSize trait from the mdnt-support crate.

This trait has a constant usize that declares the amount of cells required. Types such as AssignedCell<F,F> or [T;N] already

implement this trait, so we can leverage that for implementing the trait for AssignedFoo.

#![allow(unused)]

fn main() {

// The impl of this trait for AssignedCell shows that it, as expected, only takes up one cell.

impl<V, F> CellReprSize for AssignedCell<V, F> {

const SIZE: usize = 1;

}

// For our type we can leverage the existing implementations.

impl<F> CellReprSize for AssignedFoo<F> {

const SIZE: usize = <[AssignedNative<F>; 10]>::SIZE + <AssignedBit<F>>::SIZE; // Total 11 cells.

}

}This trait requires that the type has a known size and won’t work well with types that have dynamically sized types such as Vec.

The following pattern can be used to work around this limitation.

#![allow(unused)]

fn main() {

/// Dynamically sized version of AssignedFoo

struct AssignedFooDyn<F> {

foo: Vec<AssignedNative<F>>,

bar: AssignedBit<F>

}

/// We create a new type that has a known length.

struct LoadedFooDyn<F, const N: usize> {

foo: AssignedFooDyn<F>,

_marker: PhantomData<[(); N]>

}

impl<F, const N: usize> From<LoadedFooDyn<F, N>> for AssignedFooDyn<F> {

fn from(value: LoadedFooDyn<F, N>) -> Self {

value.foo

}

}

// And implement the trait on this new type wrapper. The other traits that we will see

// below need to be implemented on this trait as well.

impl<F, const N: usize> CellReprSize for LoadedFooDyn<F, N> {

const SIZE: usize = <AssignedNative<F>>::SIZE * N + <AssignedBit<F>>::SIZE; // Total N+1 cells.

}

}Now that we have the trait that declares the size of the type we can add support for reading, writing, or both.

For using the type as an input in a harness we need to implement LoadFromCells. And for using the type as an output

we need to implement StoreIntoCells. Both traits have 4 type parameters: F, C, E, and L. F is the type of the

field and needs to implement the ff::PrimeField trait. C is the chip we are using for the harness. In the example at the

beginning of this chapter it would be NativeChip. E is the extraction adaptor, which is a type that has a set of

associated types representing different Halo2 concepts. E must implement the Halo2Types trait in mdnt-support. Last, L does not necessarily need to implement any trait in order to satisfy either

LoadFromCells or StoreIntoCells. However, some implementations may require an instance of a Layouter and L can be constrained

to that trait (L: Layouter<F>).

#![allow(unused)]

fn main() {

impl<F, L, C, E> LoadFromCells<F, C, E, L> for AssignedFoo<F>

where

F: PrimeField,

E: Halo2Types<F>

{

fn load(

ctx: &mut ICtx<F, E>,

chip: &C,

layouter: &mut impl LayoutAdaptor<F, E, Adaptee = L>,

injected_ir: &mut InjectedIR<E::RegionIndex, E::Expression>,

) -> Result<Self, E::Error> {

// Inside this method we need to construct an instance of the type.

Ok(Self {

// We can leverage the existing implementations of the trait.

foo: ctx.load(chip, layouter, injected_ir)?,

bar: ctx.load(chip, layouter, injected_ir)?,

})

}

}

impl<F, L, C, E> StoreIntoCells<F, C, E, L> for AssignedFoo<F>

where

F: PrimeField,

E: Halo2Types<F>

{

fn store(

self,

ctx: &mut OCtx<F, E>,

chip: &C,

layouter: &mut impl LayoutAdaptor<F, E, Adaptee = L>,

injected_ir: &mut InjectedIR<E::RegionIndex, E::Expression>,

) -> Result<(), E::Error> {

// Inside this method we need to convert the type into a set of cells.

// Again, we can leverage existing implementations.

self.foo.store(ctx, chip, layouter, injected_ir)?;

self.bar.store(ctx, chip, layouter, injected_ir)

}

}

}Inside those traits the programmer has the ability of performing the conversion in different ways.

The ctx gives access to the raw cells. The chip and layouter allow performing the conversion

via some method the chip implements. For example, because the target chip implements a trait that

already has the desired logic (i.e. adding C: ThatTrait to the where bounds). Lastly, injected_ir allows

writing Haloumi IR directly for encoding semantic properties of the type. For example, the implementations for

AssignedBit and AssignedByte in midnight-circuits emits IR that constraints the value to be within the

range of the types; 0-1 and 0-255 respetively.